C-Memory Management and Usage

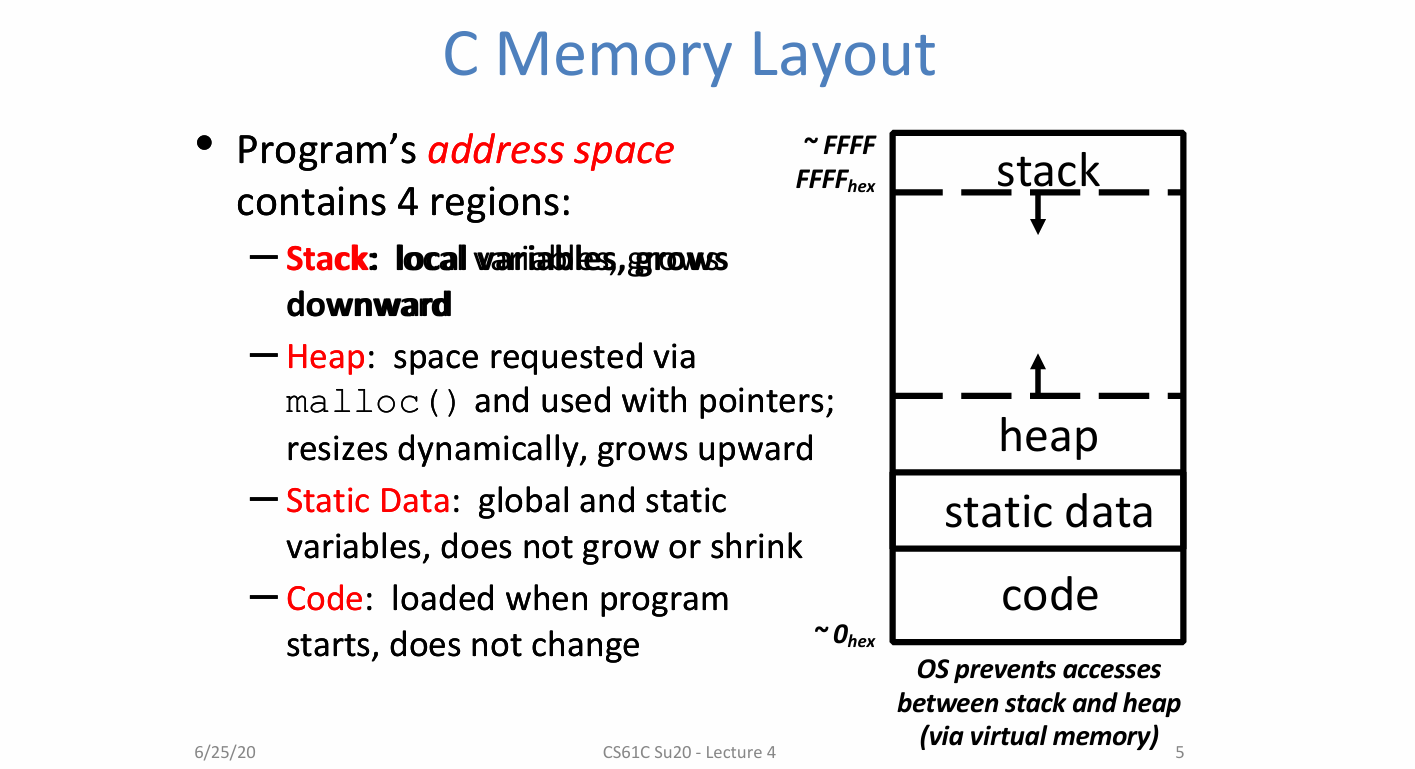

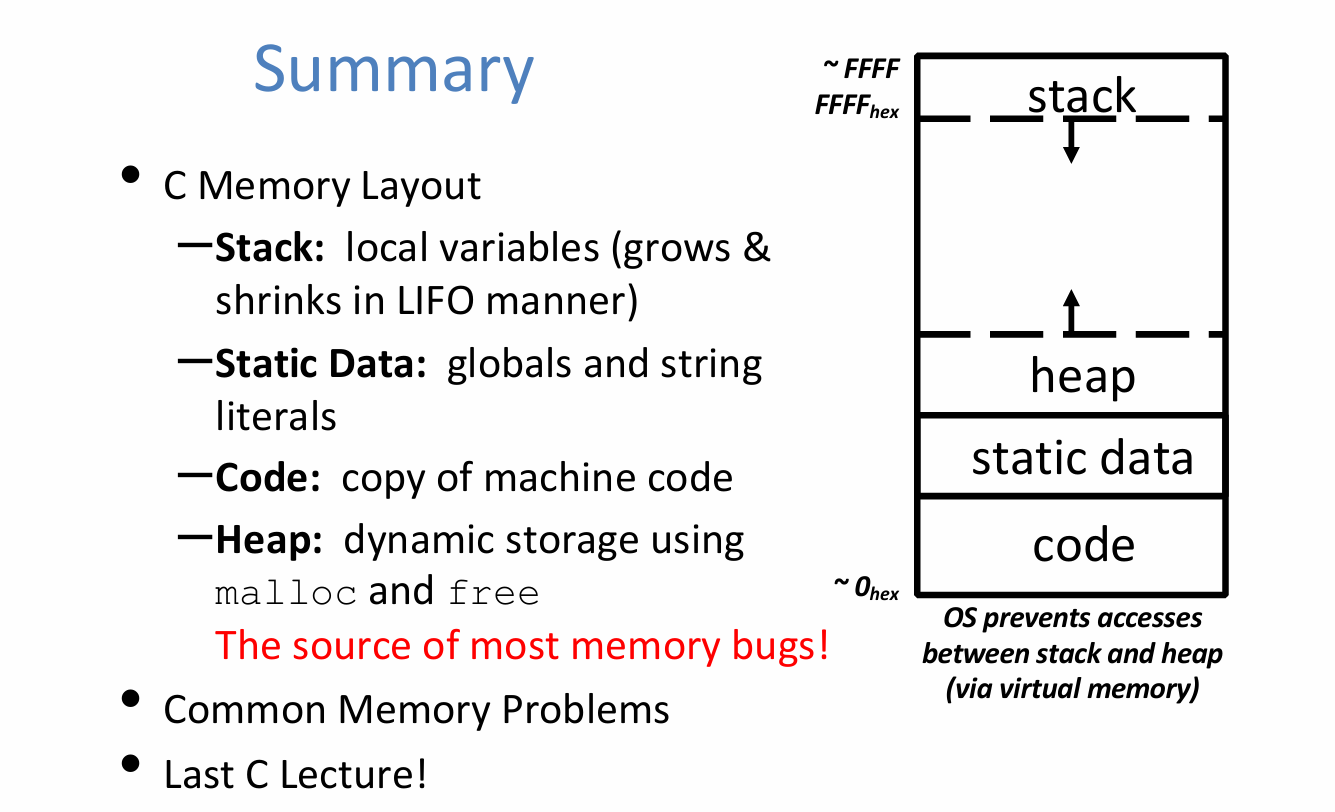

C Memory Layout

Stack:

- grow downward

- contains local variables and function frame information

Heap:

- grow upward

- you can request space via

malloc(),reallocorcallocand use the space with pointers typically - it can be dynamically resized

Static Data:

- does not grow or shrink, as this should be the same throughout the life tim of the program

- holds global and static variables

Code:

- does not change (though it technologically can)

- this is where the program is loaded to and where the program starts

OS prevents accesses between stack and heap via virtual memory

Where Do the Variables Go?

- Declared outside a function:

- Static Data

- Declared inside a function:

- Stack

main()is a function- functions have some information that it needs so it knows how to return and the parameters that are passed into it.

- Freed when function returns

- when function returns, it frees all that data off the stack, so the stack will go back to where it was before function was called

- Dynamically allocated:

- Heap

- i.e.

malloc()

1 |

|

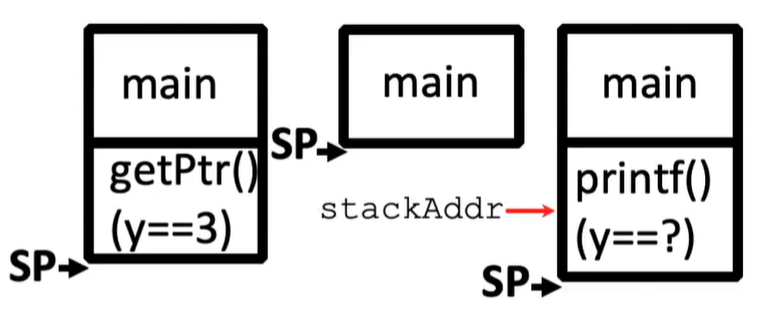

The Stack

Each stack frame is a contiguous block of memory holding the local variables of a single procedure

A stack frame includes:

- Location of caller function

- Function arguments

- Space for local variables

Stack pointer (SP) tells where lowest (current) stack frame is

When procedure ends, stack pointer is moved back (but data remains (garbage!)); frees memory for future stack frames;

Last In, First Out(LIFO) data structure

- e.g. stack frames change when functions are called……

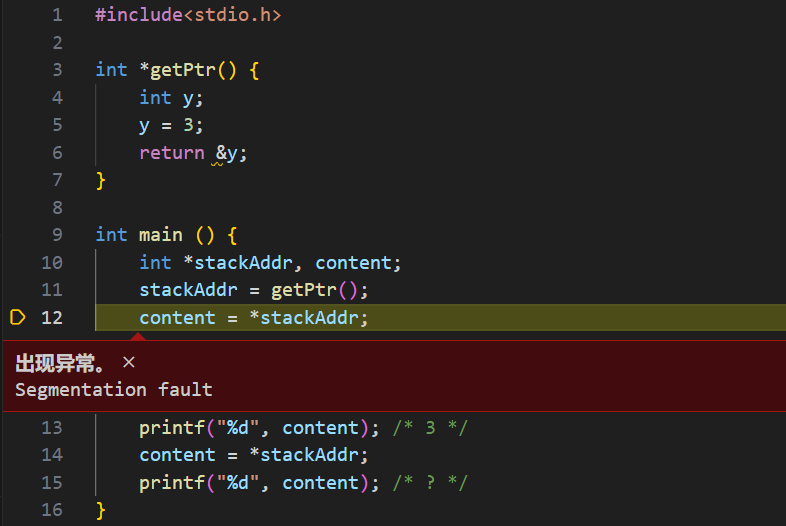

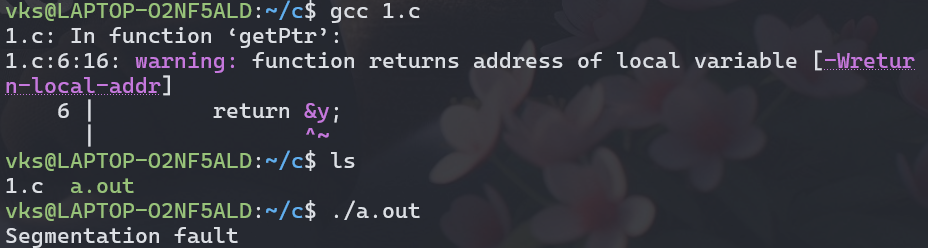

Stack Misuse Example

1 | int *getPtr() { |

- printf overwrites stack frame

- Never return pointers to local variable from functions

- Your compiler will warn you about this

- don’t ignore such warnings !

- 实际运行的效果如下:

Static Data

Place for variables that persist

- Data not subject to comings and goings like function calls

- Examples: String literals, global variables

- String literal example: char * str = “hi”;

- Do not be mistaken with: char str[] = “hi”;

- This will put str on the stack!

Size does not change, but sometimes data can

- Notably string literals cannot

Technically the static data is split into two different sections

- read-only section

- read-write section

Code

- Copy of your code goes here

- C code becomes data too!

- Does (should) not change

- Typically read only

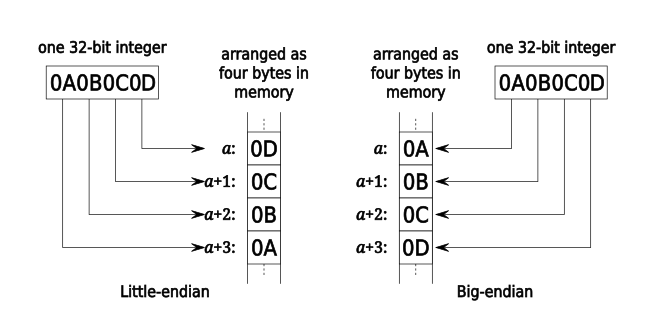

Addressing and Endianness

- The size of an address (and thus, the size of a pointer) in bytes depends on architecture (eg: 32-bit Windows, 64-bit Mac OS)

- eg: for 32-bit, have $2^{32}$ possible addresses

- In this class, we will assume a machine is a 32-bit machine unless told otherwise

- If a machine is byte-addressed, then each of its addresses points to a unique byte

- word-addresses = address points to a word

- In this class, we will assume a machine is byte-addressed unless told otherwise.

- Question: on a byte-addressed machine, how can we order the bytes of an integer in mem?

- Answer: it depends

- this concept is actually called endianness

Endianness

- Big Endian:

- Descending numerical significance with ascending memory addresses

- Little Endian

- Ascending numerical significance with ascending mem

(In this class, we will assume a machine is little endian unless otherwise stated.)

- Ascending numerical significance with ascending mem

Common Mistakes

- Endianness ONLY APPLIES to values that occupy multiple bytes

- Endianness refers to STORAGE IN MEMORY NOT number representation

- Ex: char c = 97

c == 0b01100001in both big and little endian

- Arrays and pointers still have the same order

int a[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}(assume address 0x40)&(a[0]) == 0x40 && a[0] == 1- in both big and little endian

Dynamic Memory Allocation

- Want persisting memory (like static) even when we don’t know size at compile time?

- e.g. input files, user interaction

- Stack won’t work because stack frames aren’t persistent

- Dynamically allocated memory goes on the Heap

- more permanent than Stack

- Need as much space as possible without interfering with Stack

- Start at opposite end and grow towards Stack

sizeof()

- If integer sizes are machine dependent, how do we tell?

- Use

sizeof()operator- Returns size in number of char-sized units of a variable or data type name

- Examples:

int x; sizeof(x); sizeof(int);

- Examples:

sizeof(char)is ALWAYS 1!- Note the number of bits contained in a char is also not always 1 Byte though it generally is. This means sizeof is normally returning the number of Bytes which a variable or data type is.

- In this class, we will assume a character is always 1 Byte unless otherwise stated.

- Returns size in number of char-sized units of a variable or data type name

sizeof() and Arrays

- Can we use sizeof to determine a length of an array?

- Generally no but there is an exception!

int a[61];- If I was to perform sizeof(a), I would get back the number of characters it would take to fill the array a.

- To get the number of elements, I could do:

- sizeof(a) / sizeof(int)

- This ONLY works for arrays defined on the stack IN THE SAME FUNCTION.

- This is just something fun you should know, but please do not do this! You should be keeping track of an array size elsewhere!

- Generally no but there is an exception!

Allocating Memory

- 3 functions for requesting memory:

malloc(),calloc(),andrealloc malloc(n)- Allocates a continuous block of n bytes of uninitialized memory (contains garbage!)

- Returns a pointer to the beginning of the allocated block; NULL indicates failed request (check for this!)

- Different blocks not necessarily adjacent and they might not be in order

Using malloc()

- Almost always used for arrays or structs

- Good practice to use

sizeof()and typecastingint *p = (int *) malloc(n*sizeof(int));sizeof()makes code more portablemalloc()returnsvoid *; typecast will help you catch coding errors when pointer types don’t match

- Can use array or pointer syntax to access

Releasing Memory

- Release memory on the Heap using

free()- Memory is limited, release when done

free(p)- Pass it pointer

pto beginning of allocated block; releases the whole block pmust be the address originally returned bym/c/realloc(), otherwise throws system exception- Don’t call

free()on a block that has already been released or on NULL - Make sure you don’t lose the original address

- eg:

p++is a BAD IDEA; use a separate pointer

- eg:

- Pass it pointer

Calloc

void *calloc(size_t nmemb, size_t size)- Like malloc, except it initializes the memory to 0

nmembis the number of memberssizeis the size of each member- Ex for allocating space for 5 integers

int *p = (int *) calloc (5, sizeof (int));

Realloc

- What happens when I need more or less memory in an array

void *realloc(void *ptr, size_t size)- Takes in a ptr that has been the return of malloc/calloc/realloc and a new size

- Returns a pointer with now size space (or NULL) and copies any contents from ptr

- Realloc can move or keep the address the same

- DO NOT rely on old ptr values

Dynamic Memory Example

1 |

|

Common Memory Problems

Know Your Memory Errors

- Segmentation Fault

- “An error in which a running Unix program attempts to access memory not allocated to it and terminates with a segmentation violation error and usually a core with a segmentation violation error and usually a core dump.”

- Bus Error

- “A fatal failure in the execution of a machine language instruction resulting from the processor detecting an anomalous condition on its bus. Such conditions anomalous condition on its bus. Such conditions include invalid address alignment (accessing a multi-byte number at an odd address), accessing a physical address that does not correspond to any device,or some other device-specific hardware error.”

Common Memory Problem

- Using uninitialized values

- Using memory that you don’t own

- Using NULL or garbage data as a pointer

- De-allocated stack or heap variable

- Out of bounds reference to stack or heap array

- Freeing invalid memory

- Memory leaks

Using uninitialized values

- What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10void foo(int *p) {

int j;

*p = j;

}

void bar() {

int i = 10;

foo(&i);

printf("i = %d\n", i);

} jis uninitialized (garbage), copied int*p- Using

iwhich now contains garbage

Using memory that you don’t own

1:

- What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11typedef struct node {

struct node* next;

int val;

} Node;

int findLastNodeValue(Node* head) {

while (head->next != NULL) {

head = head->next;

return head->val;

}

} - What if

headis NULL - No warnings! Just Seg Fault that needs finding!

2:

- What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10char *append(const char* s1, const char *s2) {

const int MAXSIZE = 128;

char result[MAXSIZE];

int i=0, j=0;

for (; i < MAXSIZE-1 && j < strlen(s1); i++; j++)

result[i] = s1[j];

for (; i < MAXSIZE-1 && j < strlen(s2); i++; j++)

result[i] = s2[j];

result[++i] = '\0';

return result; resultis defined on the stack(local array)- Pointer to Stack(array) no longer valid once function returns

3:

- What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12typedef struct {

char *name;

int age;

} Profile;

Profile *person =(Profile *)malloc(sizeof(Profile));

char *name = getName();

person->name = malloc(sizeof(char)*strlen(name));

strcpy(person->name,name);

... // Do stuff (that isn’t buggy)

free(person);

free(person->name) - Did not allocate space for the null terminator!

person->name = malloc(sizeof(char)*strlen(name));Want(strlen(name)+1)here. - Accessing memory after you’ve freed it. These statements should be switched.

Using Memory You Haven’t Allocated

What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7void StringManipulate() {

const char *name = “Safety Critical";

char *str = malloc(sizeof (char) * 10);

strncpy(str, name, 10);

str[10] = '\0';

printf("%s\n", str); //read until '\0'

}Write beyond array bounds

Read beyond array bounds

What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6char buffer[1024]; /* global */

int foo (char *str) {

strcpy(buffer, str);

...

}What if more than a kibi characters?

This is called BUFFER OVERRUN or BUFFER OVERFLOW and is a security flaw!!!

C String Standard Functions Revised

- Accessible with #include<string.h>

int strnlen(char *string,size_t n);- Returns the length of string (not including null term), searching up to n

int strncmp(char *str1, char *str2, size_t n);- Return 0 if

str1andstr2are identical (how is this different fromstr1 == str2?), comparing up to n bytes

- Return 0 if

char *strncpy(char *dst, char *src, size_t n);- Copy up to the first n bytes of string src to the memory at dst. Caller must ensure that dst has enough memory to hold the data to be copied

- Note:

dst = srconly copies pointer (the address)

A Safer Version

1 |

|

Freeing invalid memory

- What is wrong with these code?

1

2

3

4void FreeMemX() {

int fnh = 0;

free(&fnh);

}

- Free of a Stack variable

1 | void FreeMemY() { |

- Free of middle of block

- Free of already freed block

Memory leaks

What is wrong with this code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10int *pi;

viod foo() {

pi = (int*)malloc(8*sizeof(int));

...

free(pi);

}

void main() {

pi = (int*)malloc(4*sizeof(int));

foo();

}foo()leaks memorypiinfoo()override old pointer! No way to free those 4*sizeof(int) bytes nowRemember that Java has garbage collection but C doesn’t

Memory Leak: when you allocate memory but lose the pointer necessary to free it

Rule of Thumb: More mallocs than frees probably indicates a memory leak

Potential memory leak: Changing pointer – do you still have copy to use with free later

1 | plk = (int*)malloc(2*sizeof(int)); |

Debugging Tools

- Runtime analysis tools for finding memory errors

- Dynamic analysis tool: Collects information on memory management while program runs

- No tool is guaranteed to find ALL memory bugs; this is a very challenging programming language research problem

- You will be introduced to Valgrind in Lab 1

C Wrap-up: Linked List Example

Linked List Example

- We want to generate a linked list of strings

- this example uses structs, pointers, malloc(), and free()

- Create a structure for nodes of the list:

1

2

3

4struct Node {

char *value;

struct Node *next; //the link of the linked list

} node;

Adding a Node to the List

- Want to write addNode to support functionality as shown:

1 | char *s1 = "start", *s2 = "middle", *s3 = "end"; |

s1,s2,s3are stored in the static portion of memory,because they are string literalsthis function may take a NULL value, so we need to make sure that we handle that case, so we shouldn’t ever de-reference anything within that list

Let’s examine the $3^{rd}$ call (“start”);

1

2

3

4

5

6

7node *addNode(char *s, node *list) {

node *new = (node *)malloc(sizeof(NodeStruct));

new->value = (char *)malloc(strlen(s) + 1); //don't forget this for the null terminator

strcpy(new->value, s);

new->next = list;

return new;

}Delete/free the first node(“start”):

1

2

3

4

5

6node *deleteNode(node *list) {

node *temp = list->next;

free(list->value);

free(list);

return temp;

}

Additional Function

- How might you implement the following?

- Append node to end of a list

- Delete/free an entire list–Join two lists together

- Reorder a list alphabetically (sort)

Summary

Bonus Slides

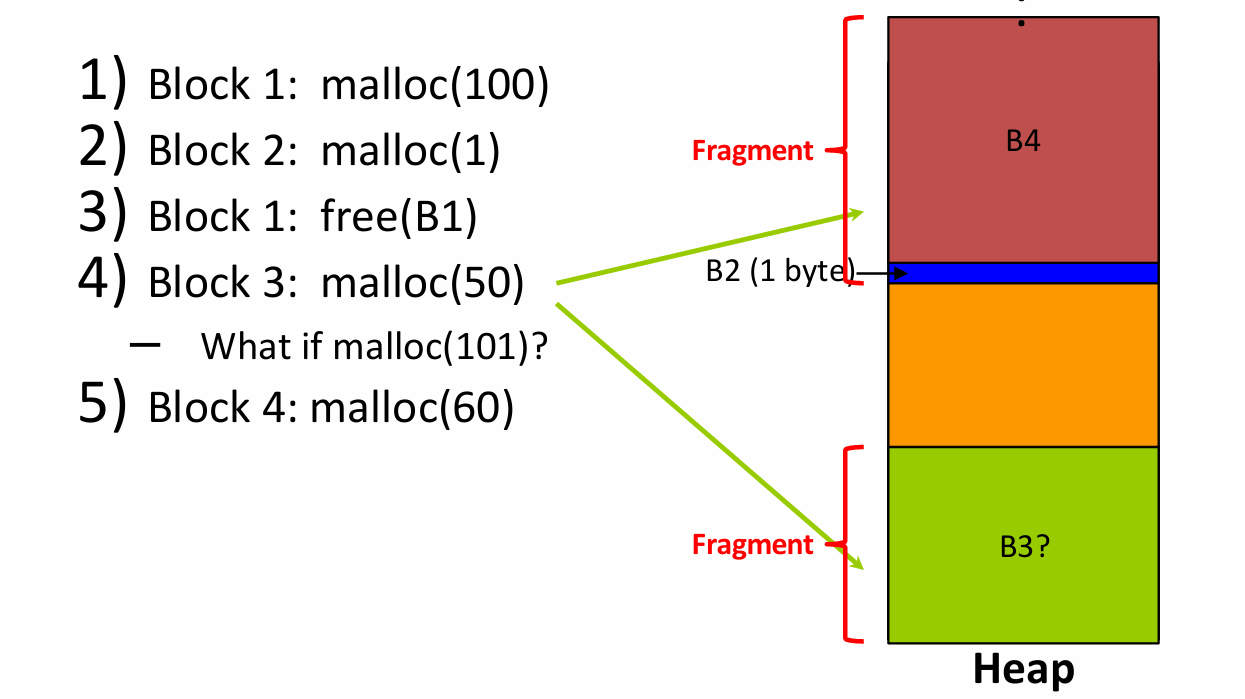

Memory Management

- Many calls to malloc() and free() with many different size blocks – where are they placed?

- Want system to be fast with minimal memory overhead

- Versus automatic garbage collection of Java

- Want to avoid fragmentation, the tendency of free space on the heap to get separated into small chunks

Fragmentation Example

Basic Allocation Strategy: K&R

- This is just one of many possible memory management algorithms

- Just to give you a taste

- No single best approach for every application

K&R Implementation

- Each block holds its own size and pointer to next block

free()adds block to the list, combines with adjacent free blocksmalloc()searches free list for block large enough to meet request- If multiple blocks fit request, which one do we use?

Choosing a Block in malloc()

- Best-fit: request Choose smallest block that fits

- Tries to limit wasted fragmentation space, but takes more time and leaves lots of small blocks

- First-fit: Choose first block that is large enough (always starts from beginning)

- Fast but tends to concentrate small blocks at beginning

- Next-fit: Like first-fit, but resume search from where we last left off

- Fast and does not concentrate small blocks at front