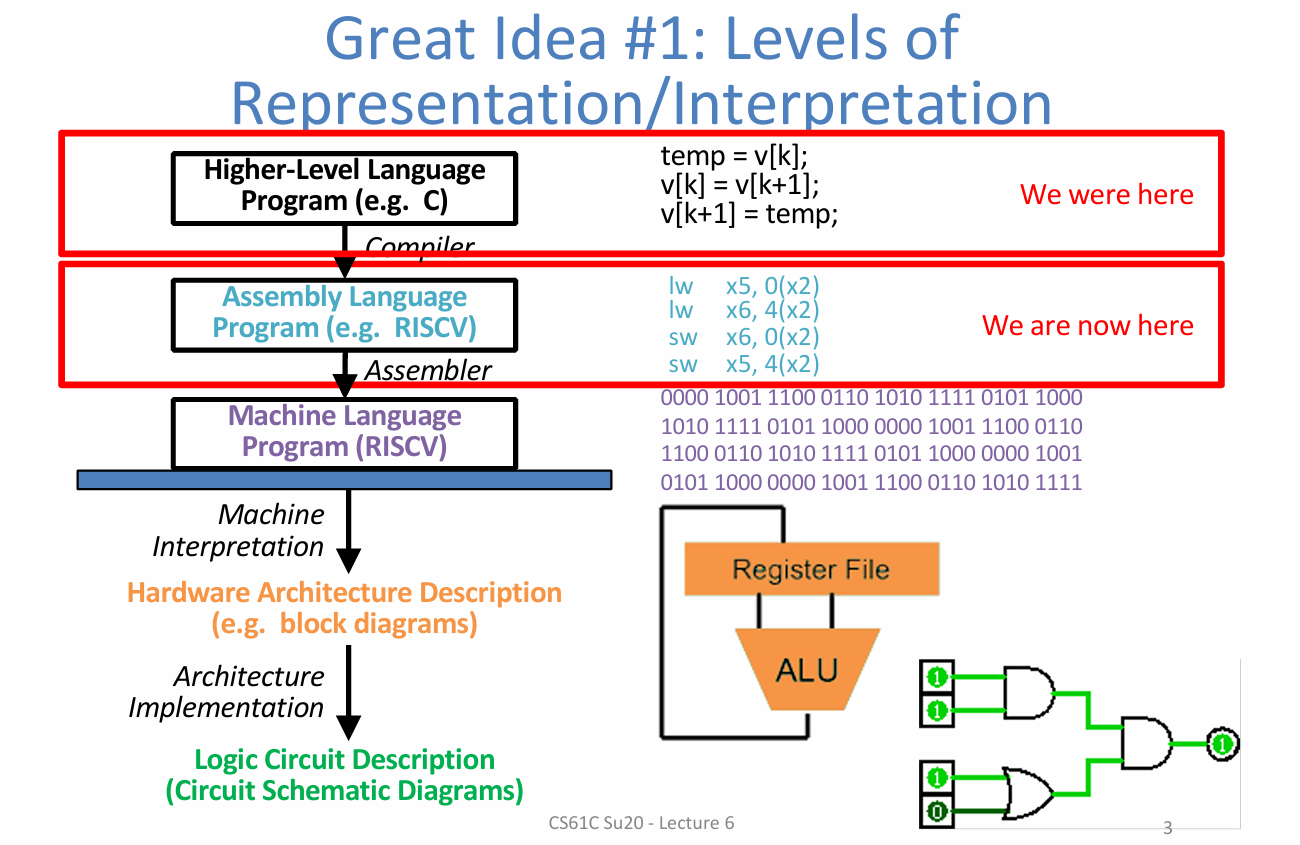

Introduction to Machine Language——RISC-V

Background

Assembly(Also known as:Assembly Language,ASM)

A low-level programming language where the program instructions match a particular architecture’s operations

Splits a program into many small instructions that each do one single part of the process

C program

1 | a = (b + c) - (d + e); |

Assembly program

1 | add t1, s3, s4 |

There are many assembly languages

A low-level programming language where the program instructions match a particular architecture’s operations

Each architecture will have a different set of operations that it supports (although there are many similarities)

Assembly is not portable to other architectures (like C is)

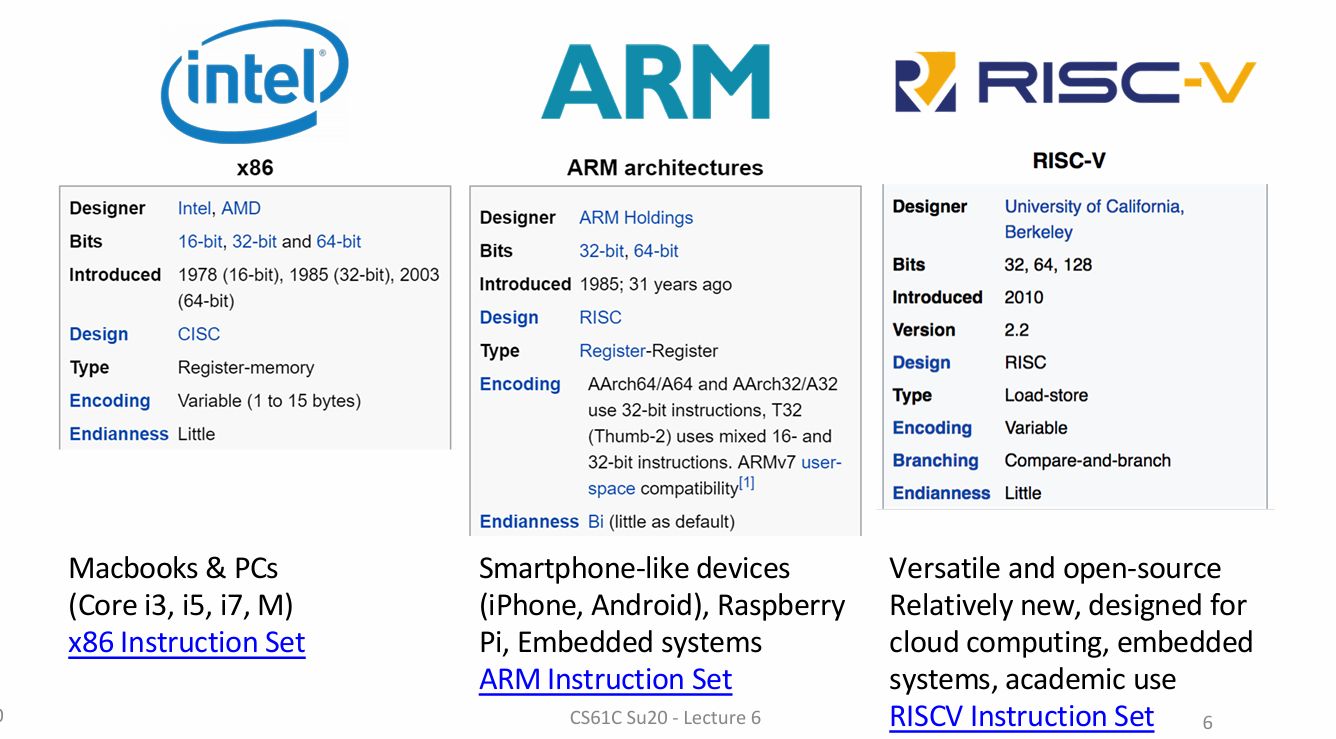

Mainstream Instruction Set Architectures

Intel is actually super long and super complicated

It is still a little bit more advantaged and it has still a lot more features, plus it is also not open source

It’s open source of pre use and it’s designed for cloud computing embedded systems and especially academic use which is really nice because it’s really nice and easy language to learn and pick up on

Which instructions should an assembly include?

There are some obviously useful instructions:

- add, subtract, and, bit shift

- read and write memory

But what about:

- only run the next instruction if these two values are equal

- perform four pairwise multiplications simultaneously

- add two ascii numbers together (‘2’ + ‘3’ = 5) 6/30/20

Complex/Reduced Instruction Set Computing

Early trend: add more and more instructions to do elaborate operations:

Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC)- difficult to learn and comprehend language

- less work for the compiler

- complicated hardware runs more slowly

Opposite philosophy later began to dominate: Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC)

- Simpler (and smaller) instruction set makes it easier to build fast hardware

- Let software do the complicated operations by composing simpler ones

RISC dominates modern computing

How important is this idea?

- RISC architectures dominate computing

- ARM is RISC and all smartphones use ARM

- Old CISC architectures (x86) are RISC-like underneath these days

- 2017 Turing Award to Patterson and Hennessy

RISC-V is what we’ll use in class

- Fifth generation of RISC design from UC Berkeley

- Professor Krste Asanovic and the Adept Lab

- Open-source Instruction Set specification

- Experiencing rapid uptake in industry and academia

- Appropriate for all levels of computing

- Embedded microcontrollers to supercomputers

- 32-bit, 64-bit, and 128-bit variants

- Designed with academic use in mind

RISC-V Resources

Full RISC-V Architecture

http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/techreports/ucb/text/EECS-2016-1.pdf

Everything we need for CS61C

https://cs61c.org/resources/pdf?file=riscvcard.pdf (“Green Card”)

Registers

Hardware uses registers for variables

- Unlike C, assembly doesn’t have variables as you know them

- Instead, assembly uses registers to store values

- Registers are:

- Small memories of a fixed size (32-bit in our system)

- Can be read or written

- Limited in number (32 registers on our system)

- Very fast and low power to access

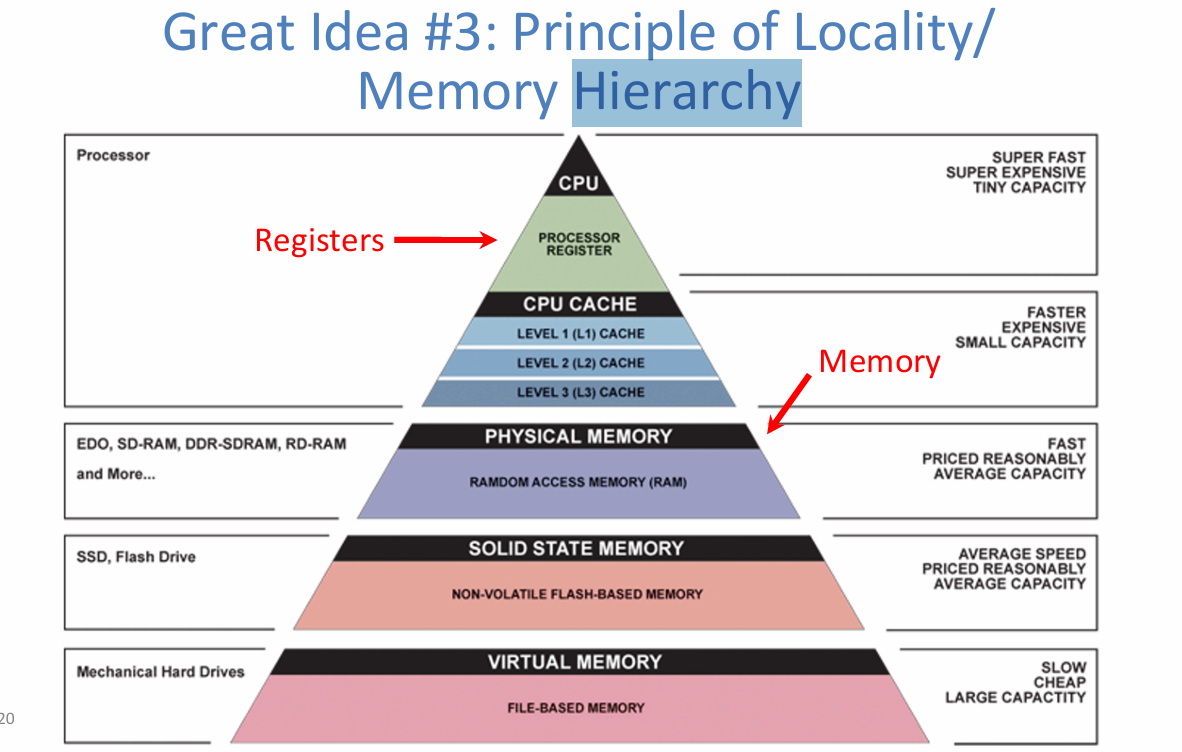

Registers vs. Memory

- What if more variables than registers?

- Keep most frequently used in registers and move the rest to memory (called spilling to memory)

- Why are not all variables in memory?

- Smaller is faster: registers 100-500 times faster

- Memory Hierarchy

- Registers: 32 registers * 32 bits = 128 Bytes

- RAM: 4-32 GB

- SSD: 100-1000 GB

Great Idea #3: Principle of Locality/ Memory Hierarchy

Register

on the CPU

CPU Cache

It is actually a little buffer between physical memory and registers. The cache is only on your CPU,so it’s a lot faster and you can still access it. But it is slower than registers, but it is definitely much faster than memory.

Physical Memory

This is somewhere else within the computer than the CPU, but it is something that is still pretty fast and used for active programs.

Solid State Memory

Such as solid state drives, flash drives those type of things, which is non-volatile, which means that you can actually unplug it from the computer and it doesn’t need power to keep the data that’s on it. These are slower than physical memory, but they are still a little bit faster than what we call file-based memory, which is like virtual memory in the sense that we have a hard drive that has different sectors on it that map data on it, or your OS maps data on it, so then you can actually store much more data.Once again, it is much slower. But the nice thing is that it’s also pretty cheap

RISCV – How Many Registers?

- Tradeoff between speed and availability

- more registers → can house more variables

- simultaneously; all registers are slower.

- RISCV has 32 registers (x0-x31)

- Each register is 32 bits wide and holds a word

Note: a word is a fixed sized piece of data handled as a unit by the instruction set or hardware of the processor. Normally a word is defined as the size of a CPU’s registers。

RISCV Register

- Register denoted by

'x'can be referenced by number (x0-x31) or name:- Registers that hold programmer variables:

- (Register ‘Name’ ⬌ Register ‘ID’/number)

- s0-s1 ⬌ x8-x9

- s2-s11 ⬌ x18-x27

- Registers that hold temporary variables:

- (Register ‘Name’ ⬌ Register ‘ID’/number)

- t0-t2 ⬌ x5-x7

- t3-t6 ⬌ x28-x31

- Other registers have special purposes we’ll discuss later

- Registers that hold programmer variables:

- Registers have no type (C concept); the operation being performed determines how register contents are treated

A Special Register

What’s the most important number?(Disclaimer: in programming)

The Zero Register

- Zero appears so often in code and is so useful that it has its own register!

- Register zero (

x0orzero) always has the value 0 and cannot be changed!- any instruction writing to

x0has no effect

- any instruction writing to

If you need to perform some operation that will change some portion of the CPU state, but you do not want to write it back to the register. You can just set the write back register to add Zero, and it will basically not do anything

Registers – Summary

- In high-level languages, number of variables limited only by available memory

- ISAs have a fixed, small number of operands called registers

- Special locations built directly into hardware

- Benefit: Registers are EXTREMELY FAST (faster than 1 billionth of a second)

- Drawback: Operations can only be performed on these predetermined number of registers

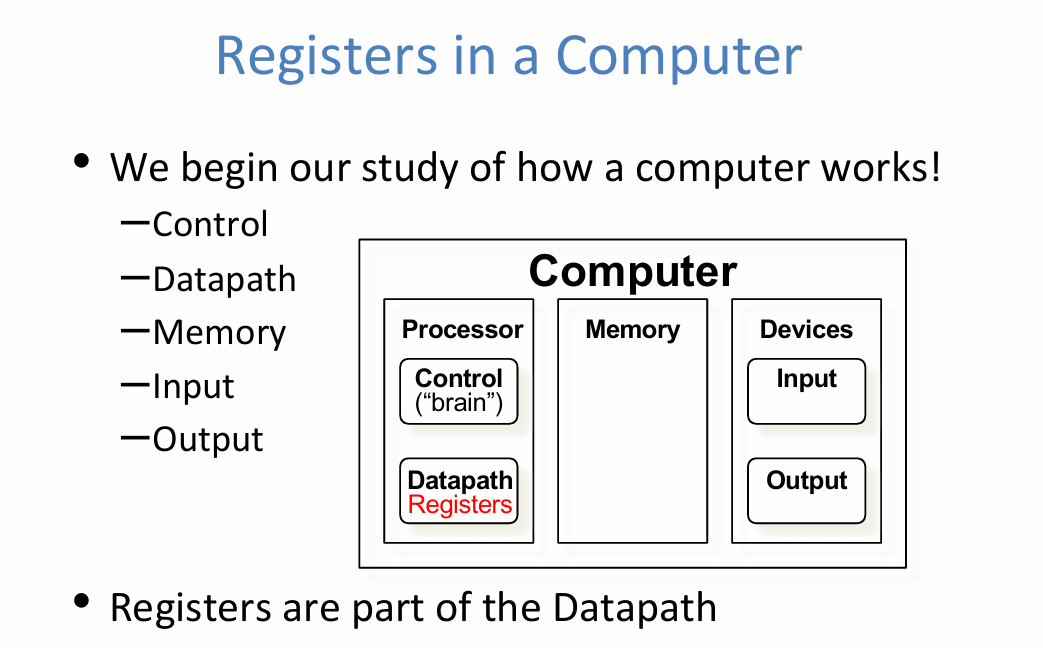

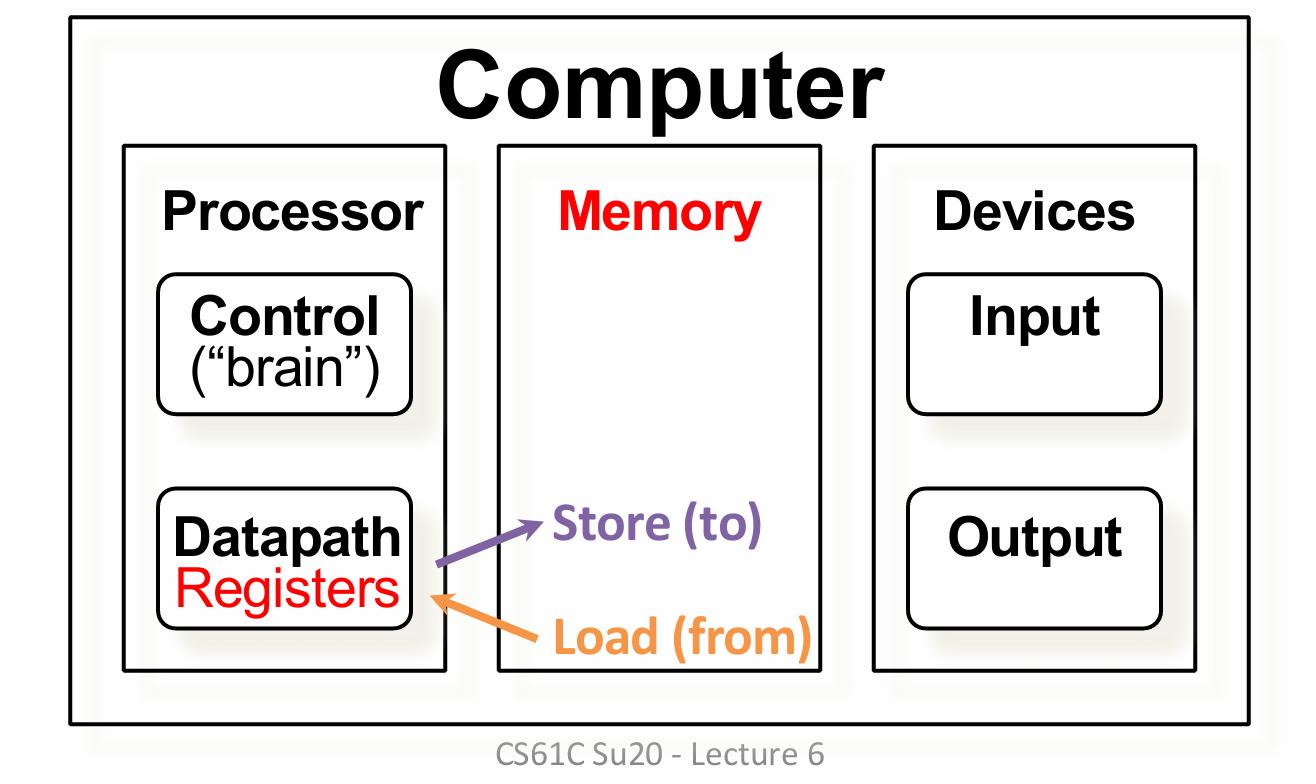

Registers in a Computer

This finally brings us to the main topic or the main idea that we’re going to be bringing up in today’s lecture – That is how a computer actually works.

So we have five big important things that a computer really has in it. We have input devices, output devices, memory, controller and a datapath.This is the basically the idea that any computer no matter how primitive or advanced it is can be divided up into these five parts.

The input devices would essentially be bringing data from the outside world into the computer system.Then this data that we got from the input devices would be put into the memory.

The datapath would be pulling from our memory using the logic from our controller, which tells the datapath what to do. And it might do some operations on this data and then store it back into memory

Finally, we need the output devices that will allow us to actually take some of the computation that we had and output it to the real world so that we can perform real jobs.

So the most common ways to connect these five components together is to use, actually, a network of buses, which is something that we won’t really cover in this class but it is something that is important to know.

Registers are a very important part of the datapath, as they are basically a small version of memory that can be used when we are doing quick operations

Assembly Code

RISCV Instructions

Instruction Syntax is rigid:

op dst, src1, src2

1 operator, 3 operands

op= operation name (“operator”)dst= register getting result (“destination”)src1= first register for operation (“source 1”)src2= second register for operation (“source 2”)

Keep hardware simple via regularity

One operation per instruction, at most one instruction per line

Assembly instructions are related to C operations (

=, +, -, *, /, &, |, etc.)Must be, since C code decomposes into assembly!

A single line of C may break up into several lines of RISC-V

Example RISC-V Assembly

1 | # Fibonacci Sequence |

- Comments use the

#symbol - Labels(

main,fib,finish) are arbitrary names that mark a section of code

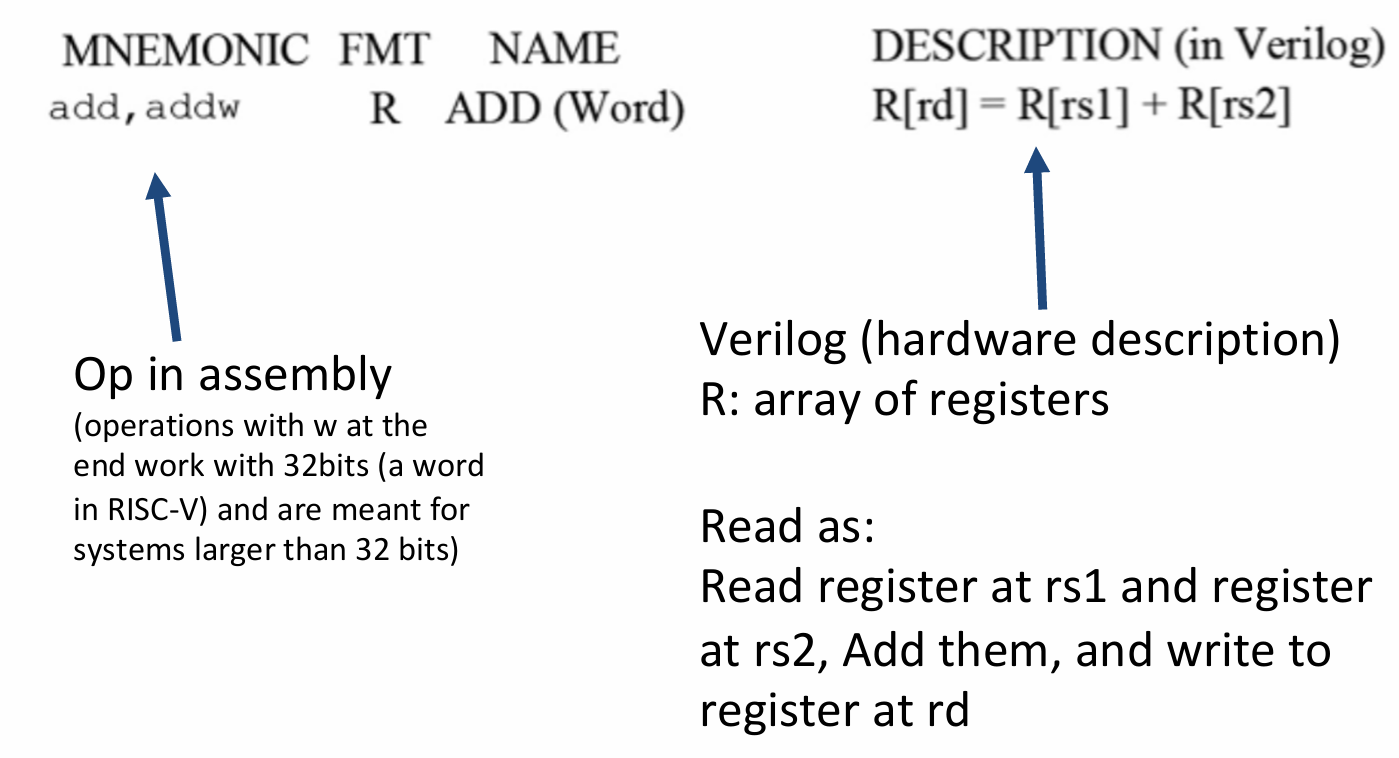

Basic Arithmetic Instructions

RISCV Instructions Example

Assume here that the variables a, b, and c are assigned to registers s1, s2, and s3, respectively

Integer Addition (add)

- C: a = b + c;

- RISCV: add s1, s2, s3

Integer Subtraction (sub)

- C: a = b - c;

- RISCV: 6/30/20 sub s1, s2, s3

Suppose a→s0,b→s1,c→s2,d→s3 and e→s4. Convert the following C statement to RISCV:

a = (b + c) - (d + e);

1 | add t1, s3, s4 |

- Ordering of instructions matters(must follow order of operations)

- Utilize temporary registers(

t1,t2)

Greencard Explanation

Immediate Instructions

- Numerical constants are called immediates

- Separate instruction syntax for immediates:

opi dst, src, imm- Operation names end with ‘i’, replace 2nd source register with an immediate

- Immediates can be up to 12-bits in size

- Interpreted as sign-extended two’s complement

- Example Uses:

- addi s1, s2, 5 # a=b+5

- addi s3, s3, 1 # c++

RISC-V Immediate Example

- Suppose

a→s0,b→s1.Convert the following C statement to RISCV:

a = (5+b)-3

1 | addi t1, s1, 5 |

- Why no

subiinstruction?

This instruction doesn’t actually exist in RISCV, but why?

subi is really just a negation of the immediate and so we could just negate the immediate when we’re programming.So why waste the space for another instruction when we can do it with one instruction already

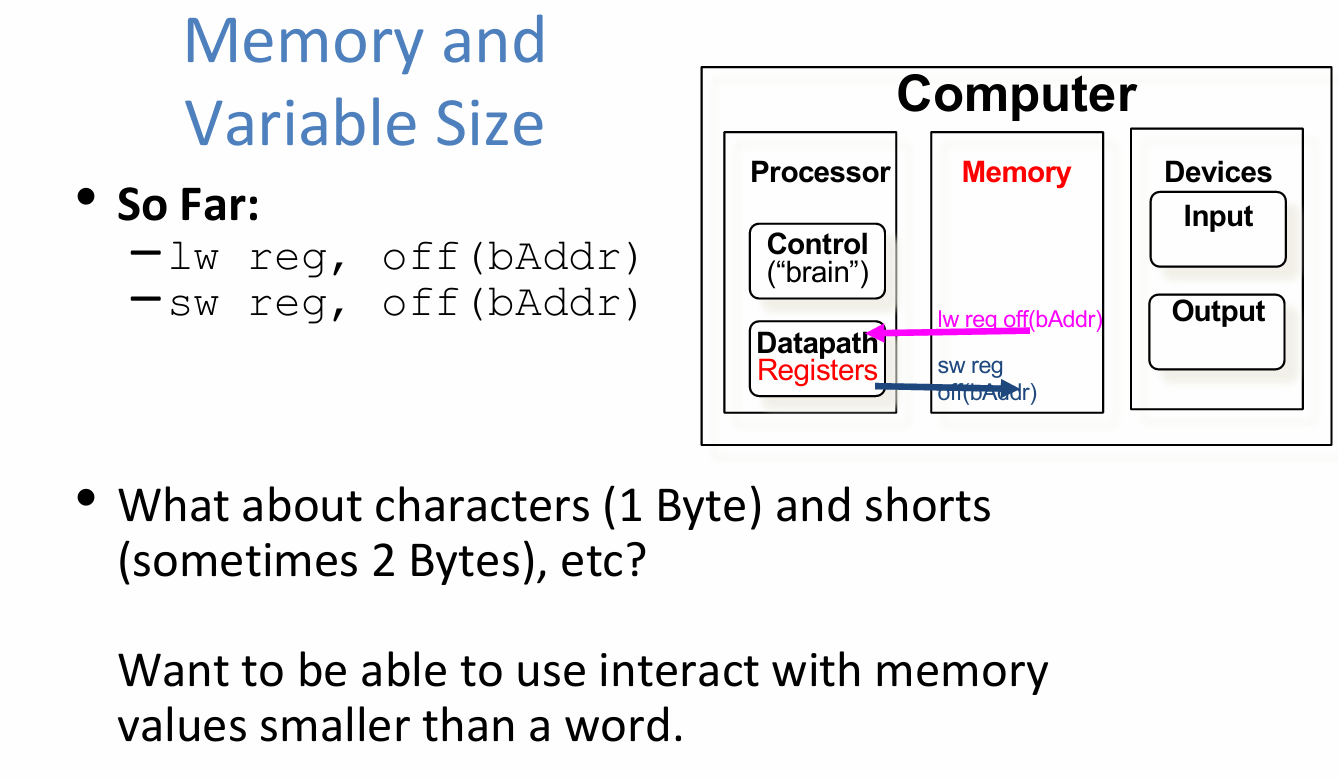

Data Transfer Instructions

Data Transfer

- C variables map onto registers; What about large data structures like arrays?

- Assembly can also access memory

- But RISCV instructions only operate on registers!

- Specialized data transfer instructions move data between registers and memory

- Store: register TO memory

- Load: register FROM memory

Five Components of a Computer

- Data Transfer instructions are between registers (Datapath) and Memory

- Allow us to fetch and store operands in memory

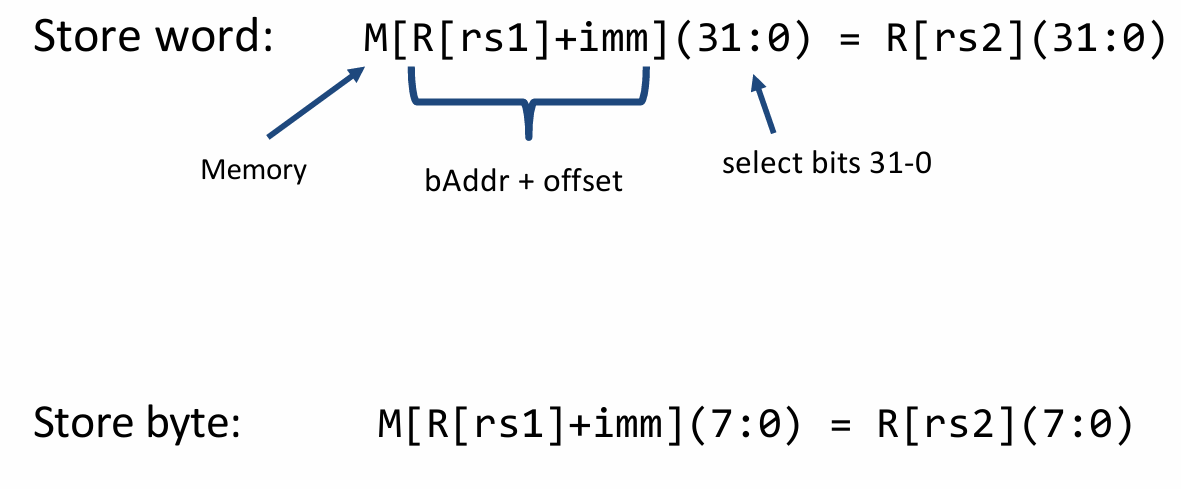

- Instruction syntax for data transfer:

memop reg, off(bAddr)memop= operation name (“operator”)reg= register for operation source or destinationbAddr= register with pointer to memory (“base address”)off= address offset (immediate) in bytes (“offset”)

- Accesses memory at address

bAddr+off - Reminder: A register holds a word of raw data (no type) – make sure to use a register (and offset) that point to a valid memory address

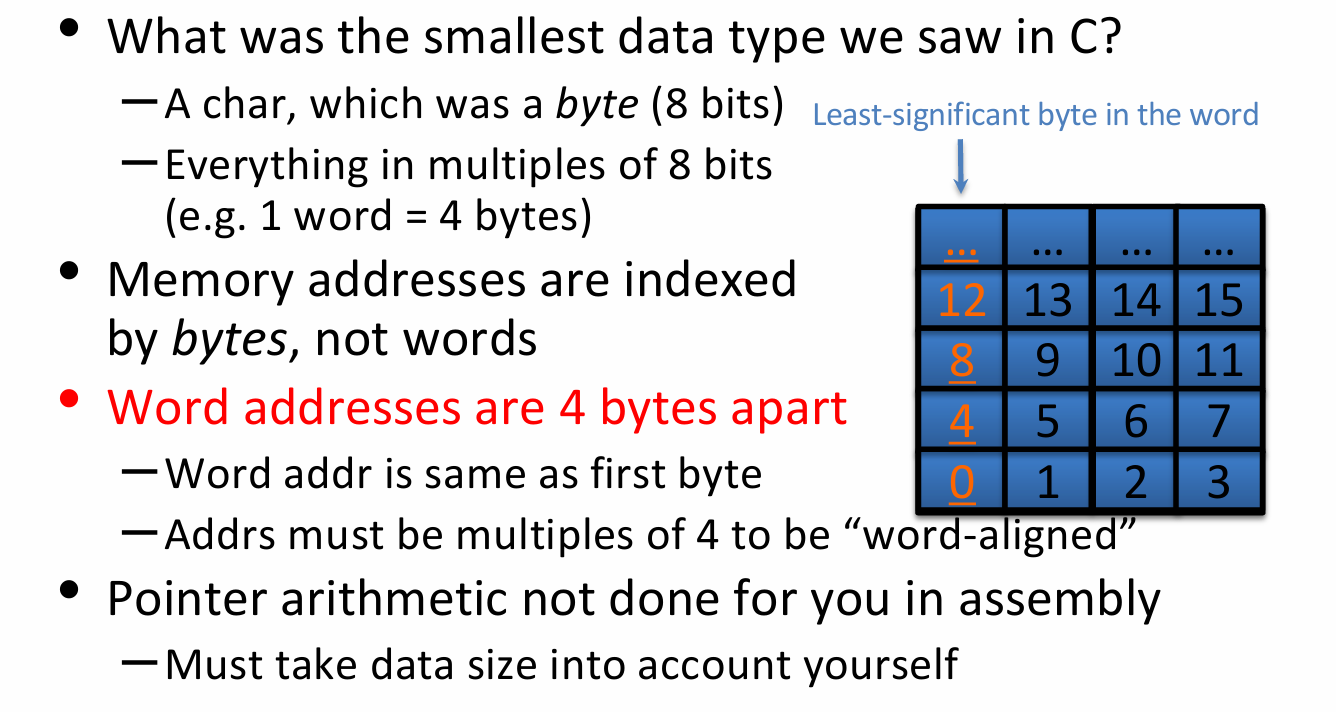

Memory is Byte-Addressed

Data Transfer Instructions

- Load Word (

lw)- Takes data at address bAddr+off FROM memory and places it into reg

- Store Word (

sw)- Takes data in reg and stores it TO memory at address bAddr+off

- Example Usage: (address of int array[]-> s3, value of b-> s2)

C:array[10] = array[3]+b; `` Assembly:lw t0,12(s3) # t0=A[3]

Values can start off in memory

1 | .data |

- .data denotes data storage

- .word, .byte, etc

- labels for pointing to data

- .text denotes code storage

List of Venus assembler directives:

https://github.com/ThaumicMekanism/venus/wiki/Assembler-Directives

Memory and Variable Size

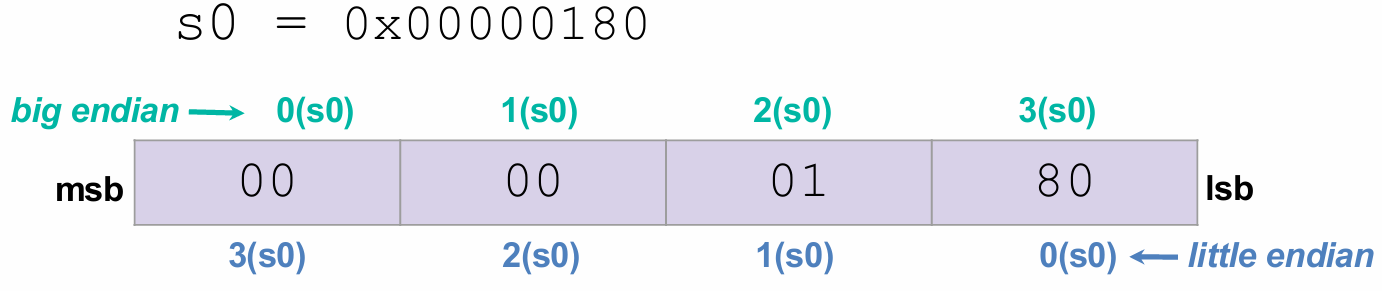

Endianness

- Big Endian: Most-significant byte at least address of word

- word address = address of most significant byte

- Little Endian: Least-significant byte at least address of word

- word address = address of least significant byte

- word address = address of least significant byte

- RISC-V is Little Endian

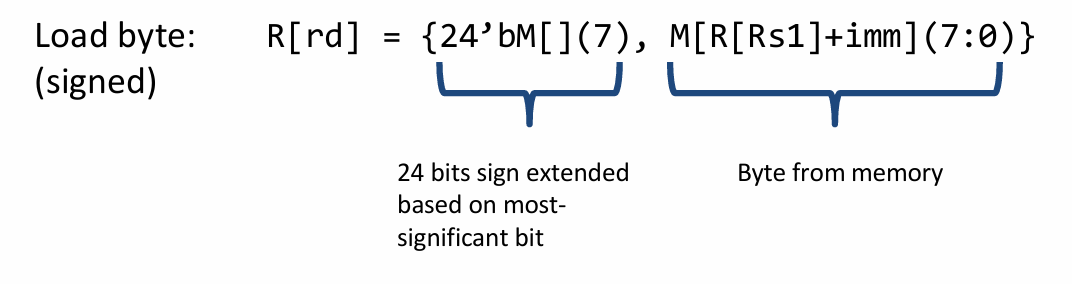

Sign Extension

- We want to represent the same number using more bits than before

- Sign Extend: Take the most-significant bit and copy it to the new bits

- 0b 11 = 0b 1111

- Zero/One Pad: Set the new bits with one/zero.

- Zero Pad: 0b 11 = 0b 0011

- One Pad: 0b 11 = 0b 1111

- Sign Extend: Take the most-significant bit and copy it to the new bits

- All base RISC-V instructions sign extend when needed

- auipc & lui technically would but they are filling the upper bits so there is nothing to fill.

Byte Instructions

| × | × | × | √ |

|---|

(lb:load bytes; sb:store bytes)

lb/sbutilize the least significant byte of the register- On

sb, upper 24 bits are ignored - On

lb, upper 24 bits are filled by sign-extension

- On

- For example, let

s0 = 0x00000180:1

2

3lb s1,1(s0) # s1=0x00000001

lb s2,0(s0) # s2=0xFFFFFF80

sb s2,2(s0) # *(s0)=0x00800180

Half-Word Instructions

| × | × | √ | √ |

|---|

lh reg, off(bAddr)“load half”sh reg, off(bAddr)“store half”- On

sh, upper 16 bits are ignored - On

lh, upper 16 bits are filled by sign-extension

- On

Unsigned Instructions

| × | × | √ | √ |

|---|

lhu reg, off(bAddr)“load half unsigned”lbu reg, off(bAddr)“load byte unsigned”- On

l(b/h)u, upper bits are filled by zero-extension

- On

Why no s(h/b)u? Why no lwu?

In a 32-bit system, it just doesn’t make sense to actually have that instruction because our register size is 32 bits which means that we are not actually going to ever have to fill in additional bits which means that a load word and a load word unsigned would be the exact same value. And so it’s not needed after all RISCV is a reduced instruction set computing architecture which means we want to reduce the number of instructions we have total. So let’s just throw out low word unsigned.

Data Transfer Greencard Explanation

!

Control Flow Instructions

Computer Decision Making

- In C, we had control flow

- Outcomes of comparative/logical statements determined which blocks of code to execute

- In RISCV, we can’t define blocks of code; all we have are labels

- Defined by text followed by a colon (e.g.

main:) and refers to the instruction that follows - Generate control flow by jumping to labels

- C has labels too, but they are considered bad style. Don’t use goto!

- Defined by text followed by a colon (e.g.

Decision Making Instructions

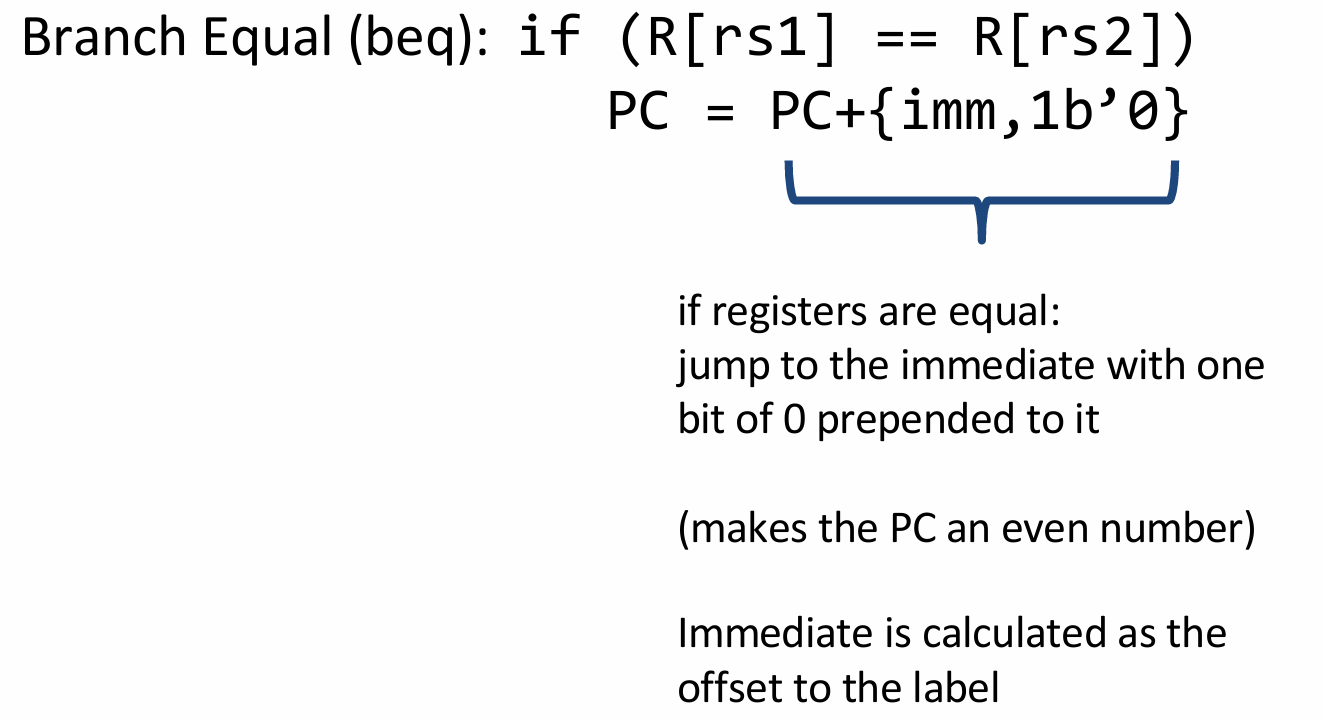

- Branch If Equal (

beq)beq reg1,reg2,label- If value in

reg1= value inreg2, go tolabel - Otherwise go to the next instruction

- Branch If Not Equal (bne)

bne reg1,reg2,label- If value in

reg1≠ value inreg2, go tolabel1

- Jump(j)

j label- Unconditional jump to

label

Breaking Down the If Else

C Code:

1

2

3

4

5if (i==j) {

a = b /* then */

} else {

a = -b /* else */ }

}In English:

- If TRUE, execute the THEN block

- If FALSE, execute the ELSE block

RISCV(

bne):1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9# i→s0, j→s1

# a→s2, b→s3

beq s0,s1, then

else: # <- this label unnecessary

sub s2, x0, s3

j end

then:

add s2, s3, x0

end:RISCV(

bne):1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9# i→s0, j→s1

# a→s2, b→s3

bne s0,s1,else

then:

add s2, s3, x0

j end

else:

sub s2, x0, s3

end:

Branching on Conditions other than (Not) Equal

Branch Less Than (blt)

blt reg1, reg2, label- If value in

reg1< value inreg2, go tolabel

Branch Greater Than or Equal (bge)

bge reg1,reg2, label- If value in

reg1>= value inreg2, go tolabel

RISC Philosophy:

- Why create a “branch greater than” if you could swap the arguments and use “branch less than”?

Breaking Down the If Else

C Code:

1

2

3

4

5if(i<j) {

a = b /* then */

} else {

a = -b /* else */

}In English:

- If TRUE, execute the THEN block

- If FALSE, execute the ELSE block

RISCV(

beg)1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10# i→s0, j→s1

# a→s2, b→s3

bge s0,s1,else

then:

add s2, s3, x0

j end

else:

sub s2, x0, s3

end:

Loops in RISCV

- There are three types of loops in C:

while, do…while, and for- Each can be rewritten as either of the other two, so the same concepts of decision-making apply

- These too can be created with branch instructions

- Key Concept: Though there are multiple ways to write a loop in RISCV, the key to decision making is the conditional branch

Program Counter

- Branches and Jumps change the flow of execution by modifying the Program Counter (PC)

- The PC is a special register that contains the current address of the code that is being executed

- Not accessible as part of the normal 32 registers

Instruction Addresses

- Instructions are stored as data in memory and have addresses!

- Recall: Code section

- Labels get converted to instruction addresses

- More on this later this week

- The PC tracks where in memory the current instruction is

Control Flow Greencard Explanation

If this condition is true then i want to update PC, which is to add to the PC the immediate value was such that the zeroth bit is a 1. So this is saying that i want to put a 1 in the zeroth bit the reason one we have this is essentially we’re padding our immediate so then it’s always even and what this means is our PC value will always be half aligned. This is important to us because we have half word instructions which we want to support for our jumping even though we might not be using them. And so this is just the general concept of RISCV where it wants us for everything will be the same simple thing without having any differences between different variations of RISCV.

Shifting Instructions

- In binary, shifting an unsigned number left is the same as multiplying by the corresponding power of 2

- Shifting operations are faster

- Does not work with shifting right/division

- Logical shift: Add zeros as you shift

- Arithmetic shift: Sign-extend as you shift

- Only applies when you shift right (preserves sign)

- Shift by immediate or value in a register

| Instruction Name | RISCV |

|---|---|

| Shift Left Logical | sll s1,s2,s3 |

| Shift Left Logical Imm | slli s1,s2,imm |

| Shift Right Logical | srl s1,s2,s3 |

| Shift Right Logical Imm | srli s1,s2,imm |

| Shift Right Arithmetic | sra s1,s2,s3 |

| Shift Right Arithmetic Imm | srai s1,s2,imm |

- When using immediate, only values 0-31 are practical

- When using variable, only lowest 5 bits are used (read as unsigned)

Shifting Instruction

1 | # sample calls to shift instructions |

Example 1:

1

2

3

4

5# lbu using lw: lbu s1,1(s0)

lw s1,0(s0) # get word

li t0,0x0000FF00 # load bitmask

and s1,s1,t0 # get 2nd byte

srli s1,s1,8 # shift into lowestExample 2:

1

2

3

4

5

6

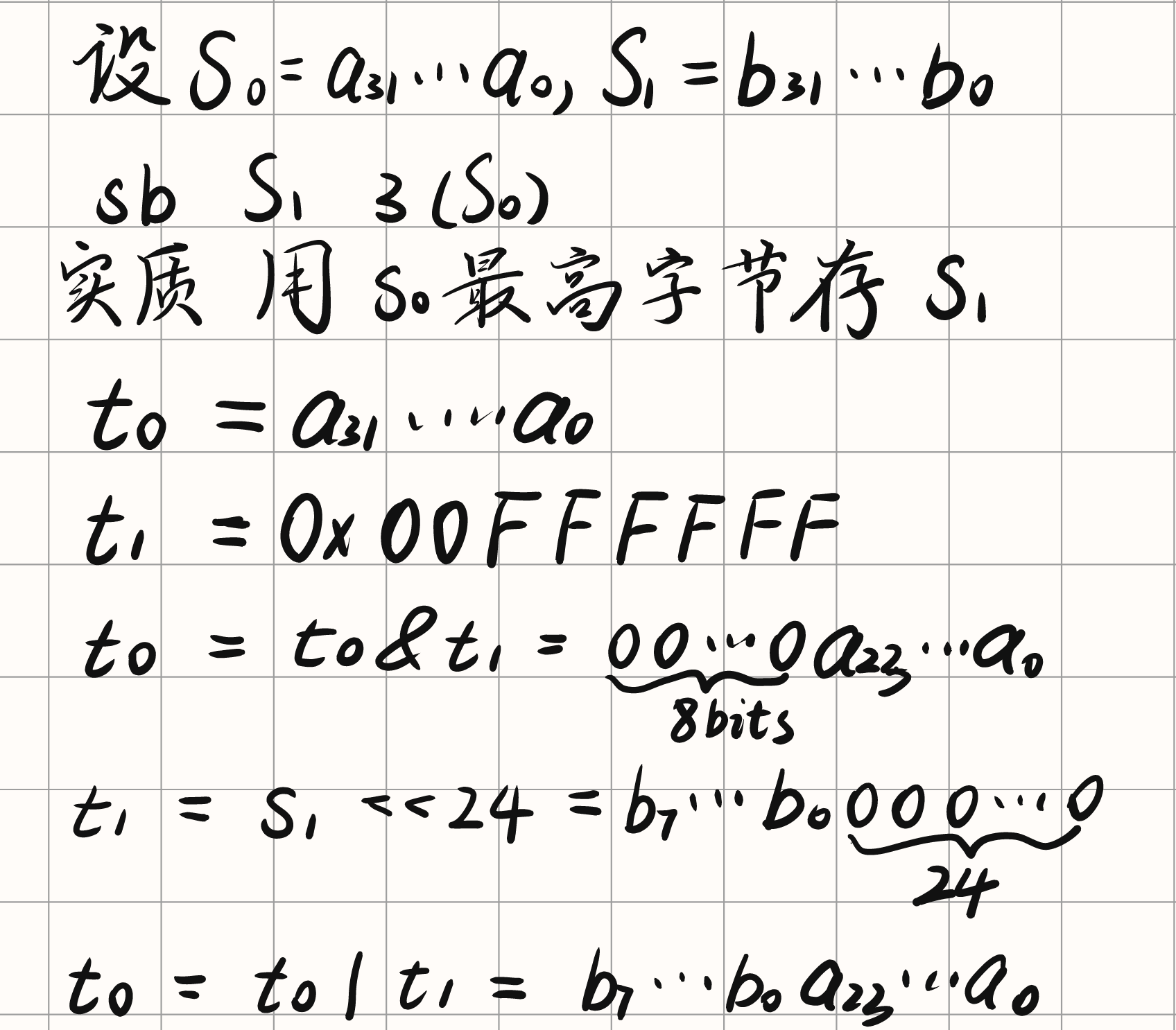

7# sb using sw: sb s1,3(s0)

lw t0,0(s0) # get current word

li t1, 0x00FFFFFF # load bitmask

and t0,t0,t1 # zero top byte

slli t1,s1,24 # shift into highest

or t0,t0,t1 # combine

sw t0,0(s0) # store back

Other useful Instructions

RISCV Arithmetic Instructions Multiply Extension

- Multiplication (

mulandmulh)mul dst, src1, src2mulh dst, src1, src2src1*src2: lower 32-bits through mul, upper 32 bits in mulh

- Division (div)

div dst, src1, src2rem dst, src1, src2src1/src2:quotient viadiv, remainder viarem

Bitwise Instructions

Note: a→s1, b→s2, c→s3

| Instruction | C | RISCV |

|---|---|---|

| And | a = b & c; |

and s1,s2,s3 |

| And Immediate | a = b & 0x1; |

andi s1,s2,0x1 |

| Or | a = b | c; |

or s1,s2,s3 |

| Or Immediate | a = b | 0x5; |

ori s1,s2,0x5 |

| Exclusive Or | a = b ^ c; |

xor s1,s2,s3 |

| Exclusive Or Immediate | a = b ^ 0xF; |

xori s1,s2,0xF |

Compare Instructions

- Set Less Than (slt)

slt dst, reg1,reg2- If value in

reg1< value inreg2,dst= 1, else 0

- Set Less Than Immediate (slti)

slti dst, reg1,imm- If value in

reg1<imm,dst= 1, else 0

Another If Else Design

C Code:

1

2

3

4

5if(i<j) {

a = b; /* then */

} else {

a = -b; /* else */

}In English

- If TRUE, execute the THEN block

- If FALSE, execute the ELSE block

RISCV:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9# i→s0, j→s1

# a→s2, b→s3

slt t0 s0 s1

beq t0,x0,else

then:

add s2, s3, x0

j end

else: sub s2, x0, s3

end:

Environment Call

ecallis a way for an application to interact with the operating system- The value in register a0 is given to the OS which performs special functions

- Printing values

- Exiting the program

- Allocating more memory for the program

A list of the ecall values supported by venus:

https://github.com/ThaumicMekanism/venus/wiki/Environmental-Calls

Summary

- Computers understand the instructions of their Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)

- RISC Design Principles

- Smaller is faster, keep it simple

- RISC-V Registers:

s0-s11, t0-t6, x0 - RISC-V Instructions

- Arithmetic:

add, sub, add - Data Transfer:

lw, sw- Memory is byte-addressed

- Control Flow: beq, bne, j

- Arithmetic: